Tagged: reunions

It Won’t Work. It Won’t Work.

As reunion tours become more audacious with each passing year, music fans are forced to imagine a limit to the return of bygone bands. The Doors, Germs, and Sublime have toured. What’s next, Nirvana, the Ramones, Blind Melon? How have the Smiths even held out this long? Rarely has a reunion received as much preemptive backlash as the upcoming competing Black Flag shows slated for this summer. One features the inimitable Ginn on guitar, with the intermediary Ron Reyes on vocals and inconsequential Gregory Moore on drums. As of now, they are the only band announced for England’s £100 Hevy Festival, along with 2 cock-rock bands and the Men in Brooklyn, and, most horrifically, plan to release a new Black Flag album.

Their rival, simply dubbed Flag, features original vocalist Keith Morris with Chuck Dukowski on bass, Bill Stevenson and Stephan Egarton from the Descendents on drums and guitar, and potentially a guest appearance from Dez Cadena. They will play the Punk Rock Bowling Festival in Las Vegas, and then tour Europe.

Choosing sides on which group is more worthy of your week’s salary will likely lead to debates in dive bars, punk clubs, and autonomous centers worldwide—is the musicality or vocals more essential? Was Rollins Black Flag’s savior or perversion? It seems many already feel there is no preferable choice. About a dozen of my friends have shared an image on Facebook reading “PLEASE DON’T” positioned familiarly around the Black Flag bars in Fitz Quadrata, a rhetorical plea for the reunion’s cancellation. Other satirical images included four erections in Flag formation next to a ruler, contesting for length, and a shirt reading “The Process of Selling Out.”

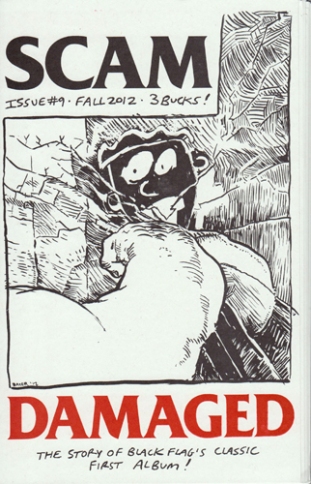

How is that a couple Black Flag reunion tours have deserved such novel ire from the punks? The answer may be found in Erick Lyle’s most recent issue of SCAM Zine, devoted entirely to the history of Black Flag’s masterpiece, Damaged. SCAM’s take on the album is like an account of the signing of the Declaration of Independence. The tyranny of the State, lead by LAPD Chief Gates and anti-drug warrior Nancy Reagan, forced a ragtag group of freedom-fighting nerds and dropouts to hole-up in a hall and produce a document that, not unlike the shards of glasses emanating from Rollins’ fist on the album’s cover, would define all trajectories of the band, the genre, L.A., and the county itself.

Following in the trend of fellow zinester vets Aaron Cometbus (Cometbus) and Al Burian (Burn Collector), Lyle has adapted a more focused and journalistic style. The challenging legibility of his handwritten intro, hand-pasted text, and Sharpie’d-in section-headers are all there, but the quality reads like something from Rolling Stone (Or LA Weekly, which published a shorter version of the zine last year for the 20th anniversary of Damaged’s release). The L.A. punk phenomenon is painted in all its lowbrow avant-garde squalor, heavy with Manson Family noir overtones and the sort of boiling youth unrest that lead to Ginn’s hateful riffs Rollins’ innovative vocal solos.

Eventually outgrowing the band, these experimental streaks were folded into an entire legacy, from Nervous Breakdown to In My Head and Raymond Pettibon’s illustrations/Ed Colver’s photography, flattened into a single iconic logo to be repeated ad nauseam in museum retrospectives and other semiotic marketplaces. Lost in the rush to historicize were the years of misery and struggle that still gives early Black Flag LPs an almost mystical power to make the listener grow a Mohawk and want to smash something. “It feels like we’re building a fucking pyramid, or trying to figure out what to put in it,” laments Lyle in his introduction. “Either way, punk was supposed to be about blowing up monuments.”

Like an archeological dig to uncover what life was like for the patriarchs, Lyle’s work is in many ways a genealogical search to understand the foundational point in every punk’s life when he hears Rise Above (or Blitzkreig Bop, or White Riot, or 500 Channels, etc) for the first time—a moment that should quite literally cause irreparable damage to the person. A reunion show may provide a night of good jams, dancing and bragging rights, but could never approach the authenticity of that first listen—engendered by a sound “sharpened like a knife,” in Rollins’ words, by the band’s daily struggles with authority.

For Lyle, the West-Coast punk phenomenon manifested itself equally in the riotous gigs and after parties at the Oki Dog parking lot, West Hollywood cliffs, and combat with police that often followed. It is in these margins, these metaphorical “lower frequencies,” that Lyle is so fond of, that gave Black Flag its authentic power, which can be no more replicated than the initial desperate skirmishes of the American Revolution. Rollins even shockingly tells Lyle that has “no good memories” of his time with Black Flag. So who are we to buy such a cheap, museum gift-shop imitation of all the violence and struggle the bars represent? To watch Ginn solo during Slip it In may be worth the price of admission, but Lyle reminds us that the heart of punk is something that cannot be bought, at least not at that price. Like the sticker on the original LP of another unfortunately recently reformed band, Crass, once said: “Pay no more than £3.00.”